Beetles lead to new manufacturing technique

The physical properties of the ultra-white scales on certain species of beetle could be used to make whiter paper, plastics and paints with far less material than is used in current manufacturing methods.

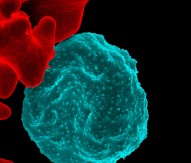

Current technology is not able to produce a coating as white as these beetles can in such a thin layer. The Cyphochilus beetle, which is native to Southeast Asia, is whiter than paper thanks to ultra-thin scales which cover its body. A new investigation, part-funded by the European Research Council, of the optical properties of these scales has shown that they are able to scatter light more efficiently than any other biological tissue known, which is how they are able to achieve such a bright whiteness.

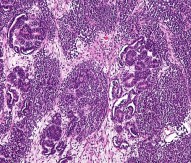

To appear as white, a tissue needs to reflect all wavelengths of light with the same efficiency. The ultra-white Cyphochilus and L. Stigma beetles produce this colouration by exploiting the geometry of a dense complex network of chitin – a molecule similar in structure to cellulose. The molecule is found throughout Nature, including in the shells of molluscs, the exoskeletons of insects and the cell walls of fungi. The chitin filaments are just a few billionths of a metre thick, and on their own are not particularly good at reflecting light.

The research, a collaboration between the University of Cambridge and the European Laboratory for non-Linear Spectroscopy in Italy, has shown that the beetles have optimised their internal structure in order to produce maximum white with minimum material. This efficiency is particularly important for insects that fly, as it makes them lighter. Over millions of years of evolution, the beetles have developed a compressed network of chitin filaments. This network is directionally-dependent, or anisotropic, which allows high intensities of reflected light for all colours at the same time, resulting in a very intense white with very little material.

Commenting, Dr Silvia Vignolini of Cambridge University’s Cavendish Laboratory, who led the research, said: “In order to survive, these beetles need to optimise their optical response, but this comes with the strong constraint of using as little material as possible in order to save energy and to keep the scales light enough in order to fly. Curiously, these beetles succeed in this task using chitin, which has a relatively low refractive index.”

In recent years, many engineers have investigated structures in Nature to inspire their designs. These findings will likely be relevant to many applications, enabling objects such as paper, plastics, paints and white-light reflectors inside new-generation displays to be made whiter, while at the same time using a smaller amount of material.

The findings are published in the journal Scientific Reports.