Our history’s future

Dr Robert Bewley discusses how the EAMENA project is working to help preserve the archaeological landscape of the Middle East and North Africa, and why it’s important that we care about our past.

In August 2015, the United Nations confirmed that so-called ‘Islamic State’ militants had near-totally destroyed the revered Temple of Bel in the Syrian city of Palmyra, an ancient temple dedicated to the Palmyrene gods and considered by UNESCO to be ‘one of the most important religious buildings of the 1st Century AD in the East [as well as] an outstanding example of Palmyrene art’.

Such attempts to censor and erase our history are far from new, but it is an issue which has perhaps never before been so at the forefront of public consciousness given the images of conflict and warfare which today dominate our TV screens and fill the pages of our newspapers.

While this has served to re-open an important discussion on the value of our cultural heritage, archaeologist Dr Robert Bewley is wary of the conversation becoming too dominated by acts of violence and ignoring the threats to our cultural heritage which are equally, if not even more, dangerous.

Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa

Bewley is the director of the EAMENA (Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa) project, a joint venture between the Universities of Oxford and Leicester aiming to record and make available information about archaeological sites and landscapes which are under threat in the Middle East and North Africa – a region which the EAMENA team estimates is home to as many as three to five million archaeological sites and which has borne witness not only to some of the first flourishes of civilisation, but also to the birth of some of the most practised religions today.

The main goal of the project, which is being supported by the Arcadia Fund, is the creation of an online database of its findings for use by researchers, archaeologists and local authorities in the region in order to both improve our understanding of the archaeology of the Middle East and North Africa and ensure that it can be better managed and preserved in the future.

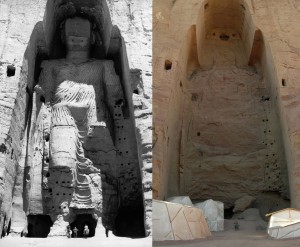

One of the Buddhas of Bamiyan before and after destruction

Identifying the threats

While much of its focus has recently centred on cultural heritage that’s been destroyed by looting and conflict in areas like Syria, Iraq and Yemen where law and order has broken down or where there is actually warfare, the project’s reach also extends to less publicised threats like agriculture (ploughing, irrigation, orchards, terracing, grazing), construction (dam building, quarrying, mining, road building and refugee encampment etc.) and natural erosion.

“Agriculture is the largest agent of destruction,” says Bewley, “and that’s because the population – particularly in the Middle East and North Africa – is rising, and not only is it rising, it’s also very fluid: there are a lot of refugees and a lot of change, and that change is rapid. People need to be fed, they need to be watered, and they need to be housed, so agriculture is crucial and finding the land for that is crucial.”

He points to a project case study in Libya, where archaeological sites in the oases of al-Jufra – including likely evidence of some of the earliest oasis settlements and agriculture in the central Sahara – are coming under increasing pressure from modern agricultural intensification. In 1975, vegetation covered an area of just 691ha; in 2011 it was close to ten times that (6,121ha).

“We can’t prevent this kind of damage, but we can mitigate it,” Bewley says. To this end, an important part of the project involves working with the relevant authorities on the ground to find out where their next infrastructure project is. “That way, we can investigate the area and identify any sites that will be affected prior to it going ahead – the hope being that steps can then be taken to limit the likely damage that will take place.” It’s an approach that’s already been working well in Europe, where for the last 30 or so years there have been schemes in place to make sure that, if someone’s building a road, an archaeological investigation is done beforehand in consideration of what might be buried underneath.

“Plans are underway to build a ring road around a city in Jordan which is home to some very important Christian remains, among other things. We went to the national authority and we said, well, how about we look along the length of the proposed road, see how much we find and then identify those sites which are directly on its route. We identified 11 sites that would be affected, and the Jordanian authorities are now looking at those sites to decide whether they want to excavate or even move the road a little bit.”

Utilising satellite imagery

The bulk of the EAMENA project involves using satellite imagery and historical photographs to discover previously unrecorded and (potentially) endangered sites. If this limits the project’s scope at all (“It isn’t an in-depth analysis, but then all archaeological surveys have limitations – there’s no such thing as a complete record or a complete excavation.”), it’s also what makes it possible in the first place. “These images are our only source of evidence in places like Yemen where access on the ground is dangerous and/or severely restricted.”

Of the ten countries so far investigated, the team has compiled records for some 100,000 sites. Bewley hopes the information they’ve collected will provide a useful resource for archaeologists to investigate further on the ground: “We operate according to the principle that, if you don’t know what you’ve got, you can’t know what you’ve lost. We’re building up a record of what’s there so that once the various conflicts are over, local archaeologists can take what we’ve found and use it to assess what remains and take the necessary steps to protect it in advance of any future events.”

He adds that the database will also provide a valuable launchpad for future research. “Say we’re recording military Roman installations, prehistorical burial grounds, the distribution of Islamic towns, for example – we can do that at a relatively high level. What we can’t do with the satellite imagery is get a really good handle on what date things are. We know what date many of the sites are because of their association with other excavated sites, but a lot of them we have no idea about.”

While some may find that frustrating, Bewley is excited about the possibilities this opens up for future generations of researchers, especially when considering how the technology available today might advance in the years to come: “It’s already incredible what we can see beneath the soil without having to excavate, but in ten, 20 years’ time, there will be even better recording techniques, so we’ll be able to record more when we excavate in the future – which is another reason why it’s important that we preserve what we can now.”

Sabratha, Libya, is under threat from coastal erosion

The value of cultural heritage

Is there a call in the meantime, then, for more legal instruments to safeguard heritage? “There is, but more important than that is enforcing the laws that are already in place. Protected (or so-called ‘protected’) sites already exist but, in reality, if someone wants to take a bulldozer to one of those sites and no-one’s looking, then they will. We’ve seen sites that have been knocked down or dug up to make way for an olive plantation, only for the plantation to then fail, so the sites have been destroyed for no reason – and protected sites at that.”

For Bewley, what the problem really comes down to is a lack of information. “If someone knows a site is important and really values it, then the landowner may decide to keep it – the issue is, how do you convince someone that their site is worth more than their crops?

“One of the positives that’s come out of the terrible things Islamic State and other such groups have been doing in the Middle East is that they’ve re-opened this discussion of why our heritage is important – why should we care about our past? The answer, usually, comes down to this question of identity. Knowing where you come from is part of what makes you who you are.

“The Iranian town of Bam was ravaged by an earthquake in 2003, and, afterwards, when the survivors were interviewed, even though they were living in tents without food or water, they all spoke about how important it was that they rebuild the core of their town. That was their identity, a part of their community.

“Something can become familiar when you see it every day, but when it’s gone it leaves a huge hole. I think that’s a very genuine feeling. It’s why people like living in historic villages or towns – because they feel a connection with the past.”

Rebuilding history

That feeling is why, in April 2016, archaeologists, politicians and members of the public alike came together in London’s Trafalgar Square to witness Palmyra’s Arch of Triumph rise again, six months after it was destroyed by Islamic State militants in October 2015.

“Understanding the past undermines and delegitimises the pretexts [extremists] use to justify these crimes and exposes them as expressions of pure hatred and ignorance,” UNESCO director general Irina Bokova said at the time of its destruction. “Palmyra symbolises everything that extremists abhor: cultural diversity, intercultural dialogue, the encounter of different peoples in this centre of trading between Europe and Asia. Despite their relentless crimes, extremists will never be able to erase history, nor silence the memory of this site that embodies the unity and identity of the Syrian people.”

The London arch (a scale replica of the 2,000-year-old, Roman-built original, meticulously recreated from Egyptian marble using 3D technology and highly detailed photographs) was masterminded by the Institute for Digital Archaeology and intended as a defiant statement that anything that can be destroyed can be rebuilt – a powerful testament to humanity’s shared history and collective achievement. But it divided critics, with many questioning the point of spending thousands of pounds on a reproduced version of the past removed from its original context and cultural significance, and denying the destruction which is already an important part of its past. If history cannot be undone, they said, it follows that it cannot be remade, either.

Bewley himself is divided about such reconstruction efforts. “I like what they did with the Buddhas of Bamiyan,” he said, in reference to the two 6th Century statues in Hazarajat, central Afghanistan, which were declared as ‘idols’ and subsequently blown up by the Taliban in 2001. In 2015, a sympathetic Chinese couple used 3D projection technology to temporarily recreate the taller Buddha in its original spot. “That was relatively inexpensive to do – especially compared to the cost of a complete rebuild – and it allowed people a glimpse of what had been there without losing sight of the religious intolerance for which it was destroyed.

“It’s never a clear cut decision, though. Reconstruction should be decided on a case-by-case basis, and in each instance it’s important to ask yourself what it is you’re trying to achieve – why are we rebuilding this? Should we do something differently? Or should we accept what happened as a part of the history of the site and leave it alone?”

Critic or fan, reconstructions like London’s Arch of Triumph and the holographic Buddha of Bamiyan are an effective reminder of what’s already been lost – and why projects like EAMENA are so important.

Dr Robert Bewley

Project Director

EAMENA Project

http://eamena.arch.ox.ac.uk/

This article first appeared in issue 19 of Pan European Networks: Science & Technology, available here.